Faster than Quick[Sort]

Can a sorting algorithm outperform QuickSort?

Of course, there are a number of restricted subdomains where known algorithms consistently outperform QuickSort: Count Sort for example, is extremely performant on sets with a limited number of (non-unique) elements; Radix Sort is another good example for integers (LSD version) and strings (MSD version).

A completely different approach is used in adaptive algorithms: rather than focusing on subdomains, these approaches exploit existing order in the arrays to cut the number of comparisons and swaps needed, and they work for any kind of data: integers, strings doubles etc...

One might frown upon the benefit of such adaptive methods. Except that real life is filled with problems that involves nearly sorted sequences. Think about a time sequence where data is gathered in parallel from several sources: does incremental map reduce ring a bell? Or about a huge sorted sequence where a constant number of elements can have their keys incremented or decremented at any time: simulation environment, evolutionary algorithms, list of polygons in a mesh could be examples of such a situation.

There are a number of well known adaptive sorting algorithms that have been proven optimal for different measures of disorder [measure of presortedness] in arrays (for an example of a measure of disorder, consider the number of inversions in an array, i.e. the number of couples (i,j) such that i < j and A[i] > A[j]). The vast majority of these algorithms are targeted to improve the upper bound on the number of comparisons needed to sort the array with respect to one or more of the measure of disorder defined in literature. Most such algorithms are really amazing from a theoretical point of view, but not as efficient in their implementation: while a notable exception is TimSort, consider Melsort as an example; it has been proven that Melsort is optimal for many measures of presortness (including a new one, the number of Encroaching Lists, defined ad-hoc after the intuition that led to _Melsort__ definition). So in theory Melsort should be fast, and in particular faster than Mergesort or even Quicksort if the input is partially ordered (the more ordered the input, the faster Melsort and adaptive algorithms in general will run).

Practical implementations of Melsort, however, have to cope with the complexity of the algorithm itself: as the saying goes, the devil is in the details, and algorithms are no exceptions - loops, conditionals, keeping track of lists and adding elements to the front of a list are operations that require computational resources, and the latter in particular is extremely expensive on most architectures (it will require O(n) time using arrays, that can be traded off for O(n) extra space - plus some overhead due to pointers and indirect addressing - using linked lists).

Long story short, Melsort implementations don't look particularly fast (to see it another way, the constant hidden in the asymptotic notation is large, very large).

This is where NeatSort comes into play. It is a nice, simple adaptive algorithm that has been proven optimal for most of the presortedness metrics in literature AND have good performance in practice: besides being simple (it is based on the same idea behind Natural Merge Sort and TimSort), special care has been dedicated to tuning it, in order to outperform non-adaptive algorithms.

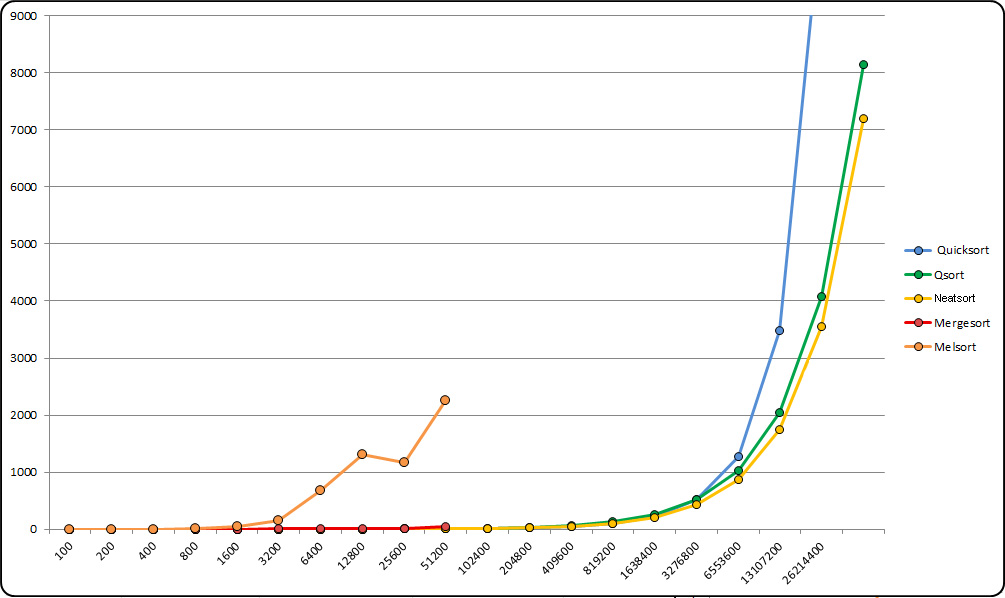

It performs so well, in fact, that proves way faster than Mergesort, and even comparable or faster than QuickSort, consistently on different hardware and OSs, even when benchmarked on random inputs.

I'm not going to delve into technical details here: If you want to take a closer look, I suggest you to read directly our first draft on arXiv.org. It's 23-pages long, but don't worry, it's filled with a lot of charts like the one above.

Here, instead, I want to share the story behind it. It's a pretty long one, in fact: it all started in January 2010, working on a graph embedding problem that involved sorting edges over and again after moving a vertex in the embedding... and it took us like forever to get to this first draft.

As I mentioned above, the initial problem to solve was sorting a sequence of edges according to their extremes' x and y coordinates. Vertices were placed on a grid and in order to find an embedding with the minimum rectilinear crossing number each of them were, in turn and randomly, moved to another cell in the grid. The algortihm was an evolutionary one, so it worked in iterations, i.e. incremental steps in which some vertex or vertices were moved around; the probability that more than a couple of vertices per iteration would be moved was very low, and most of the modifications were local (selected vertices would end up in an adjacent cell), so, after ordering the edges on iteration 0, the list of edges stayed nearly sorted at the end of each iteration, with the exception of a few edges (in particular those few ones incident on the vertices whose position had been changed).

At that time, I had never heard of adaptive algorithms, let alone Natural Merge Sort. So I kind of reinvented the wheel (in the shape of Natural MergeSort), which felt both good and frustrating. Then, I started wondering: why, if we use information about existing runs (as Natural MergeSort and TimSort do) should we discard info about where runs end, or about subsequences in reverse order? We get all that information for free, and we can as well put it to a good use.

After implementing a first version of the core algorithm, I had to test it, of course. On nearly sorted sequences, it was a game changer in comparison to QuickSort, and improved my evolutionary algorithm performance by orders of magnitude. But I was curious: what about random arrays? And there came the surprise: the later-to-be-christened NeatSort was almost as fast as my implementation of QuickSort. That's why I decided to implement my algorithm in C++ and test it against qsort library method. And again, performance was close.

NeatSort's performance way faster than Mergesort's, and similar to qsort, although not yet better: but I saw margins to improve it, and so I started studying better ways to optimize the merging of adjacent (sorted) subsequences of the array; with the invaluable insight from Prof. Cantone, who had in the meantime accepted to be involved in this project, we were able to tune Neatsort's performance and reach our goal.

By April 2010 the algorithm had reached its final structure, and by the end of 2010 optimization and tuning were perfected. Then again, it took us 4 more years to complete a first draft... mostly this delay had nothing to do with the paper itself, although a relevant amount of time was needed for testing and benchmarking, and the paper itself required in-depth study of the existing literature on the subject (you wouldn't imagine how many papers have been written on adaptive sorting...).

Anyway, it took more than 4 years, and it wasn't, by any mean, a piece of cake. But yes, you can now say that faster than QuickSort is possible - even on average, even on randomly created arrays.

Next steps:

Polishing the draft and submitting it to a journal, probably JACM;

Probably testing a Python implementation of the algorithm against Timsort;

Improving NeatSort even further.