A valuable lesson (Spotify zipfsong challenge)

I love challenges. I mean, seriously, I don't just enjoy them, I love the feeling that only solving a difficult problem gives you. It would be the perfect job for me, solving challenges 24/7: if it only existed! Well, it kind of does... kind of. In the last couple of years a few good web portals about challenges have risen to our attention, evolving from forum-like listing of real interview challenges, like Career Cup, to social experiences like Hacker Rank (formerly Interview Street), Code Eval and lately Coder Sumo, which I recently started contributing to. They are kind of slowly changing the job-offers market.

Anyway... I get it, if you don't share my enthusiasm. Sometimes challenges are frustrating, especially when you have no feedback: you might find yourself banging your head on the edge of your desk in the desperate attempt to come up with a (better?) solution, no matter what.

But, you know what? This is exactly the point. This is how you grow as a programmer: of course it doesn't always have to be the hard way, but it usually helps.

So if you are thinking that challenges are a waste of time, and they are good just for lazy, nerdy students with nothing better to do... well, think again. At the very least, it will be a good chance to improve your skills with a "new" programming language (possibly more than one...). Are you trying to learn Ruby, or to get a better grasp of C++ memory usage: go and try to solve some (hard) challenges! You'll have the chance to test your skills and have a measure of your (program's) performance, what can be better???

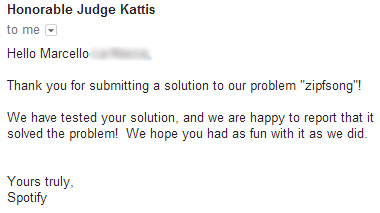

And now let's get to the point: The best part of it is that you never, never, let me say that again: never, stop learning. For example, the other day I was testing myself against Spotify puzzles. They are some of the hardest, because you don't get any feedback at all, except for the example test cases and dry messages like "Accepted", "Wrong answer", "Time limit exceeded" and "Run Time Error". It's kind of hard to understand what went wrong with your code - I suspect they want you to test your skills as a tester too.

So I was working on the mid-level one, Zipf's song. The challenge is still on, so I can't give out the solution. But I think I am in liberty to state the obvious, especially since it's already stated in the problem itself: you have a list of n items, and you have to retain the smallest (or largest?) m of them.

I was working in python, so the easiest, naive way to do so would be sorting the list and taking the first m elements, something like this:

result = sorted(list_of_stuff)[:m]

With n elements, the average running time is O(n log(n)) .

Could we do better? Of course we do. It's not even too difficult: if we use a special binary heap, bounded to hold no more than m elements (being careful to use a max heap if we are going to retain the m smallest elements, or a min heap vice versa), for each of the n elements the asymptotic running time will be O(log(m)), with at most ~2 log(m) comparisons and ~log(m) swaps s (using Sedgewick's notation instead of Big-O - the reason will be clear in a moment); building the resulting list will hence require a total of ~2n log2(m) comparisons and ~n log2(m) swap to find the m smallest elements, and an additional ~m log(m) to sort them (which is negligible if m << n). Keep in mind that, since python's sorted function uses Mergesort (an adaptive version), it will require at most ~n lg(n) comparisons.

We could do even better though: by using a d-way heap with branching factor d (say 4) we could improve the result to ~4n log4(m) comparisons and ~n log4(m) swaps.

OK, so basically if the ratio n/m is 1000, you get a speedup of a factor 10, and if n/m = 10^6, you get a speedup of a factor 20, roughly. Not bad, especially for large values of n. So on paper there is no doubt, this is the best solution. But one thing is theory, and another completely different thing is practice. I had my own library for dway-heap all ready, so I just plugged it in, with a few adjustments, and threw the answer to Spotify's automatic grader, waiting for its verdict. Uhm... "Time limits exceeded"... that's odd!

Well, after half an hour trying to figure out what was slowing it down ("maybe I can tune the function that prints the output" and similar attempt), I decided to start over. So I first tried to solve it using the naive single line instruction above. To my amazement, this time the solution was accepted.

Now, I already knew the literature is full with algorithms that works tremendously well in theory, giving us spectacular upper bounds, but that in practice are easily beaten by simpler implementations, even if they are asymptotically slower. Fibonacci's heap is probably the best known case of such a dichotomy. Quicksort is another cute example of how an asymptotically worse algorithm (Quicksort) outperforms all other sorting algorithms, including those with optimal bounds (i.e. Mergesort).

And it was also clear to me that I had developed that library with clarity and design in mind, not performance (classes in Python are notoriously slow, and moreover I even used a method call for each elements comparison, to make the lib more general purpouse!). But I never thought the difference could be so big on such a simple algorithm.

So I then decided to run some tests on small-ish lists (n ~= 1000, 10 <= m <= n, both randomly chosen at each iteration), and this are the average results, in milliseconds:

"Naive" method: 0.435998678207

d-way heap: 1434.29300451

What??? Yeah, no mistake: in practice it is 3000 times slower. :O

Now, what was making it so slow? I had a few ideas, so I run some more tests.

By eliminating the method call on comparison and replacing it with the "<" operator, we save 33% of execution time: 955.498999119 ms against 1434.29300451

By eliminating the priority field (using the element as it's own priority - always possible, we can just store tuples (priority, element) if they are distinct) and avoiding classes altogether, hence replacing the heap data structure with a simple list and its methods with functions working on a list (by assuming that the input list doesn't violate heaps properties), the execution time went down to 4.58999943733 ms: yes, indeed, an improvement of a factor 200!!!, just moving away from classes. But still 10 times slower than the naive, algorithmically slower implementation!

The best results above came using a branch factor of 4 (usually your best option with d-heaps), but I obtained a further improvement using an optimized version of a binary heap (i.e. branch factor 2) with binary shifts instead of multiplications and divisions.

By preallocating the list for the queue with m elements and keeping track of the size, instead of enlarging and shrinking it on each operation, the running time goes down to 3.8200107002 and... and that's about it, that's as good as it gets, no further improvement is likely possible (I tried a few more tricks like using statically typed, fixed size array.array instead of lists, but with no gain)

OK, what did just happen here? Well, if you were going to say that a simple theoretically inefficient algorithm trumped the best of breed... you'd be right. Almost.

Since now the heap algorithm is much faster, I could run it on larger and larger lists.

For n ~= 1000000, 100 <= m <= n, the difference becomes smaller: 48.1549966335 ms against 268.325001717 ms

For n ~= 10000000, 100 <= m <= n, it's even smaller: 607.869996786 ms against 2738.20800114 ms, basically a factor 4.5 instead of 10

For n ~= 100000000, 100 <= m <= n: 8180,0300026 ms vs 31933.19999815 ms (~3.9)

So as n increases, the asymptotic behaviour becomes more and more important, as one would expect. And, of course, this was not the best use for d-way heaps: they are especially useful when you must keep a priority queue alternating insert and extract-top operations, and perhaps repeated decrease-key operations (like for Dijkstra algorithm).

But I believe these are the key points, the real lesson to learn:

You must be very very careful when moving from theory to implementation!

Do not make assumptions, do not take anything for granted. If performance is critical, test, tune, and test again, even against naive but simpler solutions.

Carefully evaluate the size of your inputs: for smaller values, simple solution, with small "constants" factor in their big-Oh, will probably outperform complicated algorithms; for very large instances, like millions of billions of elements, you'll probably need to care about asymptotic behaviour.

STAY AWAY FROM PYTHON CLASSES!!! In fact, I rewrote the lib mentioned above in the form of a package supporting separate sets of functions for min and max heaps. The result is less elegant and requires the user to be careful and thoughtful, since there is no encapsulation nor controls. But it is much faster than the class version!

Moreover, "we are all among adults" is sort of Python motto, right? Still, mistakenly using the min-heap version of put on a max-heap produces unpredictable misbehaviour! To restrict the possibility of errors, a helper function to create heap is provided, and only the pseudo object returned (or structures alike them) can be passed to the package functions.

You can find it here, together with its unit-testing module.